Something universal among runners is that we’re never satisfied. There’s always room for improvement. Rather than bask in glory or cower in defeat, we head back to the drawing board. How can I be better next time? That was certainly the case with Kodiak 100, where my race didn’t go as well as I’d liked, and I’ll apply lessons learned during that effort at San Diego 100.

Reflecting on Kodiak 100, besides my trifecta of falls, there were three key areas that impacted my performance, and I’m documenting them here so as not to forget (say it LOUDER for the people in the back). They are: 1) Weak power hiking; 2) Insufficient fueling; 3) Poor Aid Station efficiency.

1) Power Hiking

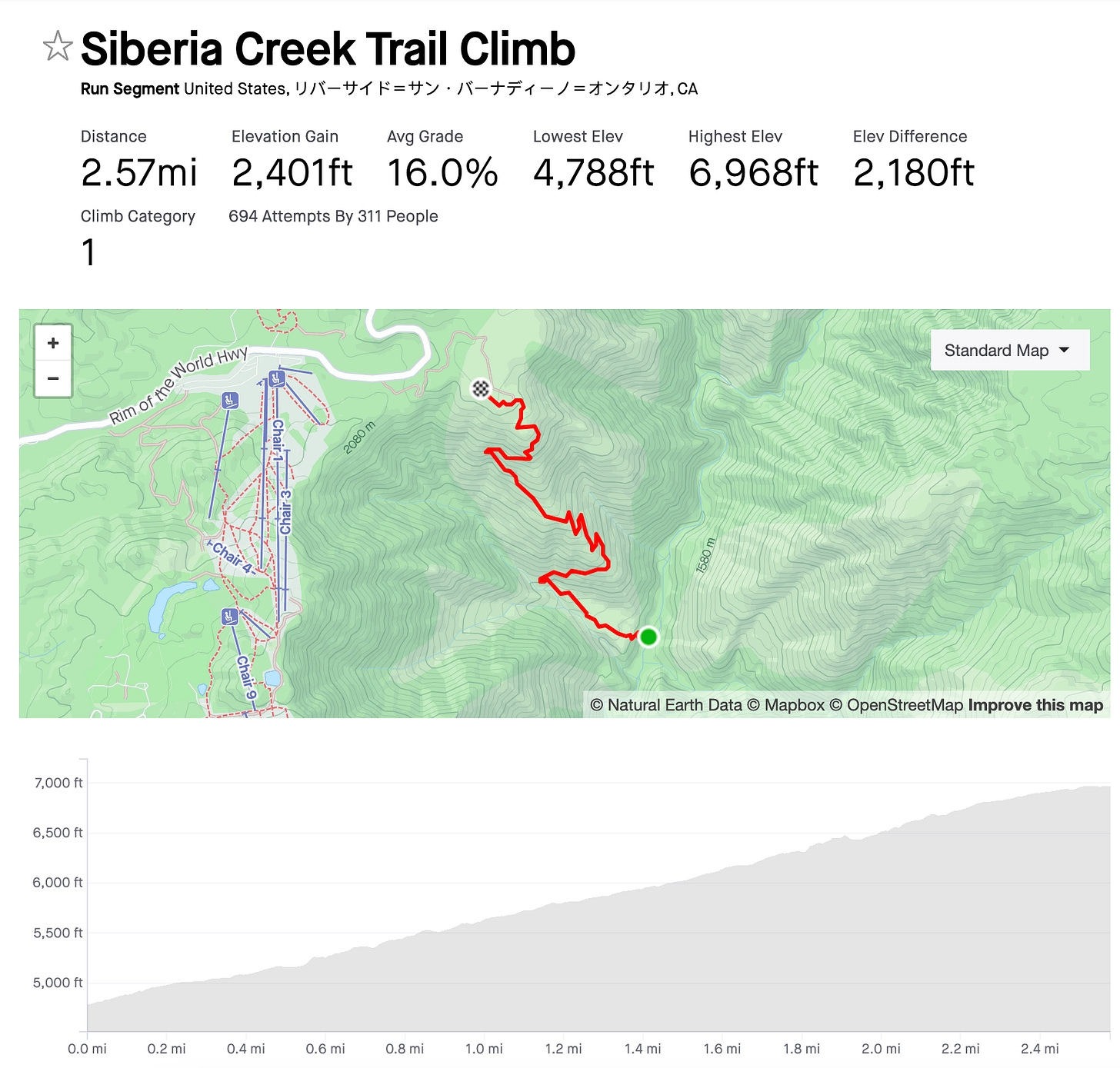

In ultrarunning, it seems nothing will expose your weakness like a big climb (or a long descent). For me, this shortcoming reared its head during a 2.6-mile climb with 2,400 feet of ascent at Kodiak 100.

At mile 21, after we bottomed out at Siberia Creek (and after I’d already fallen twice), we began our two-and-a-half-mile, 2,400-foot ascent out of the canyon. Knowing that we would be rewarded with a fun and runnable section after we completed the climb, I stepped into the climb with enthusiasm.

Just two-and-a-half hard miles, and then I’ll be home free for the next 30, I thought.

Despite my enthusiasm, however, I ended up being under-equipped. As I wound my way up the steep switchbacks, gravity was pulling me back down to toward the creek, and it seemed each step was a struggle.

I did what I’d practiced: Bend at the waist, lean forward, hands on knees – power hike! Forward progress, yes, but I was quickly losing steam, fading. I’d hear other racers – men and women alike – close in on me, joy in their voices and spring in their steps, as if climbing 950 ft per mile didn’t phase them. Some had poles, others did not. And they were picking me off, one at a time.

I promise I was doing my best, but I couldn’t generate enough umph. It took me just over an hour to cover those 2.6 miles. Again, not the worst on the planet, but it felt slow, like watching the last bit of ketchup inch its way down a bottle of Heinz 57.

So, as I train for San Diego 100, I’m going to get in more race-specific climbing and also strengthen my glutes. To be sure, I incorporated a fair amount of vert in the build to Kodiak, but going into the race I could’ve done more – especially during weekend back-to-back long efforts. Here’s what this means:

· More hill repeats on trails during weekend runs

· More power hiking on weekends, in order to get that adaptation

· More strength-training exercises like Mountain Legs

2) Under Fueling

Weakness on the climbs wasn’t my only shortcoming at Kodiak. Fueling, or lack thereof, also hamstrung my effort. Though my plan was sound, with multiple sources of carbs and calories on my person and in my drop bags, significant nausea hit at mile 80, and I did not fully recover before I crossed the finish.

Though Kodiak is a mountain race, with much of it run over 6,000 feet above sea level, I don’t think the altitude was the source of my nausea. My stomach felt fine through mile 70. I believe it turned south between miles 70 and 80 simply because I under fueled earlier in the day.

Though I was always sipping on liquid calories, and taking gels roughly once every 45 minutes, that worked out to only 100-150 calories and 30-50 grams of carbs per hour. That’s low but sufficient during regular training runs. But under racing conditions, that represents roughly half the fueling that many elites take. I was under-fueling, and the deficiency was compounding throughout the race.

A lack of caffeine also played a role – especially late into the night. I distinctly remember leaving the Sugarloaf Aid Station at mile 82, around 2:00 a.m. I was cold, severely under fueled (because nausea made food unpalatable), and up way past my bedtime. I had a Clif Shot Espresso gel in my drop bag. But because I hadn’t trained with it, I elected not to take it, as I was nervous that it would make me even more nauseous.

As I nearly fell asleep while slowly climbing the next section in a trance, I regretted not taking it. Those 100 calories and 100 mg of caffeine would have done wonders. (I know this because a month later, during the 4x4x48, where I ran 4 miles every 4 hours for 48 hours, I took the espresso-flavored gel before my 12th and final run, and it ended up being my best leg of the entire challenge.)

At the Bear Mountain Aid Station (mile 88), after bonking so hard in the preceding miles, I forced down 2 pancakes. The carbs and calories weren’t enough to cover the fueling deficiency fully, but it did help close the gap.

To help better manage fueling at San Diego 100, I’m going to train with a wider variety of calorie- and carb-dense fuels. That way on race day I will have trained my gut – and my palate – to be able to take on the extra fueling needed for better performance. In addition to my current mix of Gu and Clif Shot gels and high-carb drink mixes, I’m working into the program hydrogels from Precision Hydration and whole food “gels” from Muir Energy (variety is key!).

3) Aid Station efficiency

An aid stations is a welcome – and sometimes tricky – fixture to navigate during an ultra. After spending hours alone on the trail, I find so much joy when reaching an aid station. It’s beacon of light and a wonderful sensation to be welcomed by the volunteers, especially when reaching an aid station in the cold of a dark night. They literally pull out a chair and offer all kinds of delicious snacks.

While I am beyond grateful for the support, for San Diego 100 I will need to make it clear that my mission when I enter an aid station is to get in and out as quickly as possible. I’m on the clock!

This isn’t to say that I will neglect my needs. But I will need to move through with urgency: refill my bottles, restock my pack, jam down some Aid Station faire, and get on my way. And only sit if absolutely necessary.

One way to pull off this strategy is to fill my bottles with whatever electrolyte mix they have on hand. (At Kodiak, I literally made custom drink-mix concoctions at every aid station, or the volunteers made them for me).

In addition, refilling my hydration bladder was also problematic (the race mandated that racers carried at least 2L of fluid between certain aid stations, where the gap was more than 9 miles). I will check the race book to see if there are similar requirements, and if there are, I will find a creative way to be compliant.

Of course, if I’m fortunate to have a crew, I will be able to get through aid stations with NASCAR-like quickness.

Either way, Aid Stations are a critical part of an ultra – and how you spend your time in them can make or break your race. This time around, I’m going to use them to make my race.

Forward Progress

We runners are a stubborn bunch – and often our own worst critics. We analyze our performances and pick them apart, mile by mile. We relive key moment in our heads and map out what we could have done differently. If only… But, buried in that neurosis is optimism and a belief that we can do better. And I will.